When the future becomes today

Abstract

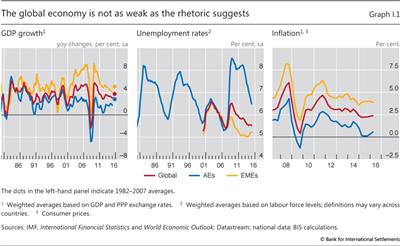

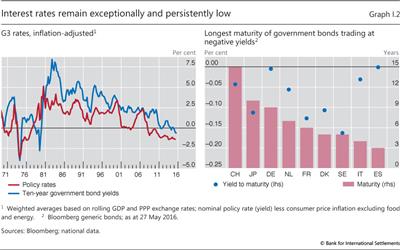

Judged by standard benchmarks, the global economy is not doing as badly as the rhetoric sometimes suggests. Global growth continues to disappoint expectations but is in line with pre-crisis historical averages, and unemployment continues to decline. Less comforting is the longer-term context - a "risky trinity" of conditions: productivity growth that is unusually low, global debt levels that are historically high, and room for policy manoeuvre that is remarkably narrow. A key sign of these discomforting conditions is the persistence of exceptionally low interest rates, which have actually fallen further since last year.

The year under review saw the beginnings of a realignment in the forces driving global developments: partly in response to US monetary policy prospects, global liquidity conditions began to tighten and the US dollar appreciated; financial booms matured or even began to turn in some emerging market economies (EMEs); and commodity prices, especially the oil price, dropped further. However, global prices and capital flows partly reversed in the first half of this year even as underlying vulnerabilities remained.

There is an urgent need to rebalance policy in order to shift to a more robust and sustainable expansion. A key factor in the current predicament has been the inability to get to grips with hugely damaging financial booms and busts and the debt-fuelled growth model that this has spawned. It is essential to relieve monetary policy, which has been overburdened for far too long. This means completing financial reforms, judiciously using the available fiscal space while ensuring long-term sustainability; and, above all, this means stepping up structural reforms. These steps should be embedded in longer-term efforts to put in place an effective macro-financial stability framework better able to address the financial cycle. A firm long-term focus is essential. We badly need policies that we will not once again regret when the future becomes today.

Full text

The global expansion continues. But the economy still conveys a sense of uneven and unfinished adjustment. Expectations have not been met, confidence has not been restored, and huge swings in exchange rates and commodity prices in the past year hint at the need for a fundamental realignment. How far removed are we from a robust and sustainable global expansion?

When put in perspective, standard metrics indicate that macroeconomic performance is not as dire as the rhetoric may sometimes suggest (Graph I.1). True, global growth forecasts have been revised downwards once more, as they consistently have been since the Great Financial Crisis. But growth rates are not that far away from historical averages, and in a number of significant cases they are above estimates of potential. In fact, once adjusted for demographic trends, growth per working age person is even slightly above long-run trends (Chapter III). Similarly, unemployment rates have generally declined and in many cases are close to historical norms or estimates of full employment. And although inflation is still below specific targets in large advanced economies, it may be regarded as broadly in line with notions of price stability. Indeed, the downbeat expression "ongoing recovery" does not do full justice to how far the global economy has come since the crisis.

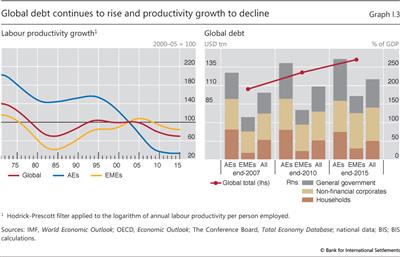

Less comforting is the context in which those economic gauges are evolving and what they might tell us about the future. One could speak of a "risky trinity": productivity growth that is unusually low, casting a shadow over future improvements in living standards; global debt levels that are historically high, raising financial stability risks; and a room for policy manoeuvre that is remarkably narrow, leaving the global economy highly exposed.

As noted in last year's Annual Report, a highly visible and much debated sign of this discomfort has been exceptionally and persistently low interest rates. And they have fallen even further since then (Graph I.2, left-hand panel). Inflation-adjusted policy rates have edged deeper below zero, continuing the longest postwar period in negative territory. Moreover, the Bank of Japan has joined the ECB, Sveriges Riksbank, Danmarks Nationalbank and the Swiss National Bank in adopting negative nominal policy rates. And at the end of May, close to $8 trillion in sovereign debt, including at long maturities, was trading at negative yields - a new record (Graph I.2, right-hand panel).

These interest rates tell us many things. They tell us that market participants look to the future with a degree of apprehension; that despite huge central bank efforts post-crisis, inflation has remained stubbornly low and output growth disappointing; and that monetary policy has been overburdened for far too long. The contrast between global growth that is not far from historical averages and interest rates that are so low is particularly stark. That contrast is also reflected in signs of fragility in financial markets and of tensions in foreign exchange markets.

Interpreting the evolution of the global economy is fraught with difficulties, but it is necessary if we are to identify possible remedies. As we have in recent Annual Reports, we offer an interpretation using a lens that focuses on financial, global and medium-term aspects. We suggest that the current predicament in no small measure reflects the failure to get to grips with hugely costly financial booms and busts ("financial cycles"). These have left long-lasting economic scars and have made robust, balanced and sustainable global expansion hard to achieve - the hallmark of uneven recovery from a balance sheet recession. Debt has been acting as a political and social substitute for income growth for far too long.

This interpretation argues for an urgent rebalancing of policy to focus more on structural measures, on financial developments and on the medium term. A key element of this rebalancing would be a keener appreciation of the cumulative impact of policies on the stocks of debt, on the allocation of resources and on the room for policy manoeuvre. For it is this lack of appreciation that constrains options when the future eventually becomes today. Intertemporal trade-offs are of the essence.

In this Annual Report, we update and further explore some of these themes and the tough analytical and policy challenges they raise. This chapter provides an overview of the issues. It looks first at the evolution of the global economy during the past year. It then digs deeper into some of the forces at play, putting the elements of needed macroeconomic realignments in a longer-term perspective and assessing the risks ahead. The chapter concludes with the resulting policy considerations.

The global economy: salient developments in the past year

By and large, the performance of the global economy in the year under review traced patterns seen in previous years, with signs of recurrent tension between macroeconomic developments and financial markets.

Global output again grew more slowly than expected, although at 3.2% in 2015 it was only slightly lower than in 2014 and not far from its 1982-2007 average (Chapter III). On balance, the projected rotation of growth from emerging market economies (EMEs) to advanced economies failed to materialise, as advanced economies did not strengthen enough to compensate for weakness in commodity-exporting EMEs. At the time of writing, consensus forecasts point to growth strengthening gradually in advanced economies and bouncing back more strongly in EMEs.

Labour markets proved more resilient. In most advanced economies, including all the largest jurisdictions, unemployment rates continued to decline. By the end of 2015, the aggregate rate was down to 6.5%, its level in 2008 before the bulk of its surge during the crisis. Even so, in some cases, unemployment remained uncomfortably high, notably in the euro area and among the young. The picture was more mixed in EMEs, with major weakness as well as some strength, but their aggregate unemployment rate edged up slightly.

This differential performance - improving employment but moderate output growth - points to weak productivity growth, the first element of the risky trinity (Graph I.3, left-hand panel). Productivity growth remained on the low side, continuing the long-term decline that had been visible at least in advanced economies and that had accelerated in those hit by the crisis.

Inflation stayed generally subdued, except in some EMEs - notably in Latin America - that experienced sharp currency depreciations (Chapter IV). In the largest advanced economies that are home to international currencies, underlying (core) inflation, while remaining below targets, moved up even as headline rates remained considerably lower. Low inflation also prevailed in much of Asia and the Pacific and in smaller advanced economies.

Once more, a critical factor in these developments was the further drop in prices for commodities, especially oil. After some signs of a pickup during the first half of last year, oil prices resumed their plunge before recovering somewhat in recent months. The generalised drop in commodity prices helps explain growth patterns across commodity exporters and importers (Chapter III). The resultant contraction in commodity exporters was only partly offset by currency depreciations against the backdrop of an appreciating US dollar. Similarly, the commodity price declines shed light on the wedge that opened up between headline and core measures and on why the most uncomfortably high inflation rates went hand in hand with weak economic activity (Chapter IV).

In the background, debt in relation to GDP continued to increase globally - the second element of the risky trinity (Graph I.3, right-hand panel). In the advanced economies worst hit by the crisis, some welcome reduction or stabilisation in private sector debt tended to be offset by a further rise in the public sector. Elsewhere, a further increase in private sector debt either accompanied that in the public sector or outweighed the decline in the latter.

The financial sector's performance was uneven (Chapter VI). In advanced economies, banks quickly adapted to the new regulatory requirements by further strengthening their capital base. Even so, non-performing loans remained very high in some euro area countries. Moreover, even where economic conditions were favourable, bank profitability was somewhat subdued. Worryingly, banks' credit ratings have continued to decline post-crisis, and price-to-book ratios still typically languish below 1. In the past year, insurance companies did not fare much better. In EMEs, with their generally more buoyant credit conditions, the banking picture looked stronger. That said, it deteriorated where financial cycles had turned.

Financial markets alternated phases of uneasy calm and turbulence (Chapter II). The proximate cause of the turbulence was anxiety about EME growth prospects, especially China's. A first bout of anxiety took hold in the third quarter and, after markets had regained their composure, a second appeared in early 2016 - one of the worst January sell-offs on record. This was followed by a briefer, if more intense, turbulent phase in February, when banks found themselves at the centre of the storm. Triggers included disappointing earnings announcements, regulatory uncertainty concerning the treatment of contingent convertible securities (CoCos) and, above all, worries about banks' profits linked to expectations of persistently lower interest rates following central bank moves. Thereafter, markets stabilised, notably boosting asset prices and capital flows to EMEs once more.

The alternation of calm and turbulence left a clear imprint on financial markets. By the end of the period, most equity markets were down even as price/earnings ratios remained rather high by historical standards. Credit spreads were considerably higher, especially in the energy sector and in many commodity-exporting countries. The US dollar had appreciated against most currencies. And long-term yields were plumbing new depths.

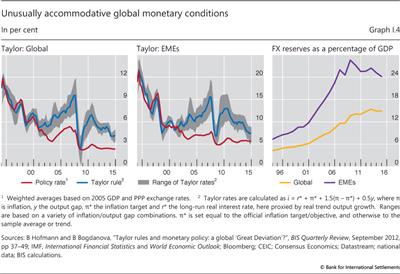

Against this backdrop, the room for macroeconomic policy manoeuvre narrowed further - the third element of the risky trinity. This applies most obviously to monetary policy (Chapter IV). True, the Federal Reserve began to raise the policy rate after having kept it effectively at zero for seven years. But it subsequently signalled that it would tighten more gradually than originally planned. At the same time, monetary policy eased further in other key jurisdictions through both lower interest rates and a further expansion in central bank balance sheets. The reduction in room for manoeuvre also applies to some extent to fiscal policy (Chapters III and V). With the fiscal stance in advanced economies turning, on balance, more neutral or supportive of economic activity in the short term, the process of long-term consolidation paused. In the meantime, fiscal positions weakened substantially in EMEs, especially commodity exporters.

The global economy: interpretation and risks

It is tempting to look at the global economy over time as a set of unrelated frames - or, in economists' parlance, as a series of unexpected shocks that buffet it about. But a more revealing approach may be to look at it as a movie, with clearly related scenes. As the plot unfolds, the players find that what they did in the early part of the movie inevitably constrains what they can reasonably do next - sometimes in ways they had not anticipated. Again, in economists' parlance, it is not just "shocks" but "stocks" - the underlying circumstances that have evolved - that matter. This suggested perspective may help to explain not only how we got here, but also what the future might have in store.1 It is worth briefly reviewing the key features of the movie.

Interpretation: a movie

As argued in previous Annual Reports, the movie that best describes the current predicament of the global economy probably started many years back, even before the crisis struck. And, in many respects, we may not yet have stepped out of the long shadow of the crisis.

The crisis appears to have permanently reduced the level of output. Empirical evidence increasingly indicates that growth following financial crises may recover its previous long-term trend, but the output level typically does not. So, a permanent gap opens up between the pre-crisis and post-crisis trend of the output level (Chapter V). On this basis, given the almost unprecedented breadth and depth of the recent crisis, it would be unrealistic to think that output could regain its pre-crisis trend. Hence the persistent disappointing outcomes and gradual ratcheting down of potential output estimates.

All this would imply that, at least for a while, the crisis reduced the growth of potential output. The persistent and otherwise puzzling slowdown in productivity growth is consistent with this. There are many candidate explanations for the mechanisms at work. But a possibly underappreciated one is the legacy of the preceding outsize financial boom (Chapter III). Recent BIS research covering more than 20 advanced economies and 40 years suggests three conclusions: financial booms can undermine productivity growth as they occur; a good chunk of the erosion typically reflects the shift of labour to sectors with lower productivity growth; and, importantly, the impact of the misallocations that occur during a boom appears to be much larger and more persistent once a crisis follows.

The corresponding effects on productivity growth can be substantial. Taking, say, a five-year boom and five post-crisis years together, the cumulative impact would amount to a loss of some 4 percentage points. Put differently, for the period 2008-13, the loss could equal about 0.5 percentage points per year for the advanced economies that saw a boom and bust. This roughly corresponds to their actual average productivity growth during the same window. The results suggest that, in addition to the well known debilitating effects of deficient aggregate demand, the impact of financial booms and busts on the supply side of the economy cannot be ignored.

In this movie, the policy response successfully stabilised the economy during the crisis, but as events unfolded, and the recovery proved weaker than expected, it was not sufficiently balanced. It paid too little attention to balance sheet repair and structural measures relative to traditional aggregate demand measures. In particular, monetary policy took the brunt of the burden even as its effectiveness was seriously challenged. After all, an impaired financial system made it harder for easing to gain traction, overindebted private sector agents retrenched, and monetary policy could do little to facilitate the needed rebalancing in the allocation of resources. As the authorities pushed harder on the accelerator, the room for manoeuvre progressively narrowed.

This had broader implications globally. For one, with domestic monetary policy channels seemingly becoming less effective, the exchange rate rose in prominence by default (Chapter IV). And resistance to unwelcome currency appreciation elsewhere helped spread exceptionally easy monetary conditions to the rest of the world, as traditional benchmarks attest (Graph I.4): easing induced easing. In addition, the exceptionally easy monetary stance in the countries with international currencies, especially the United States, directly boosted credit expansion elsewhere. From 2009 to the third quarter of 2015, US dollar-denominated credit to non-banks outside the United States increased by more than 50%, to about $9.8 trillion; and to non-banks in EMEs, it doubled to some $3.3 trillion. Global liquidity surged as financing conditions in international markets eased (Chapter III).

In sum, we witnessed a rotation in financial booms and busts around the world after the crisis. The private sector in the advanced economies at the heart of the crisis slowly started to deleverage; elsewhere, especially but not only in EMEs, the private sector accelerated the pace of releveraging as it left behind the memory of the 1997-98 Asian crisis. Signs of unsustainable financial booms began to appear in EMEs in the form of strong increases in credit and property prices and, as in previous episodes, foreign currency borrowing. Currency appreciations failed to arrest the tide. In fact, as BIS research suggests, they may have even encouraged risk-taking, as they seemingly strengthened the balance sheet of foreign currency borrowers and induced lenders to grant more credit (the "risk-taking channel") (Chapters III and IV).

Crucially, the prices of commodities, especially oil, reinforced these developments - hence all the talk about a commodity "supercycle" (Chapter III). On the one hand, the strong growth of more energy-intensive EMEs drove prices higher. China, the marginal buyer of a wide swathe of commodities, played an outsize role as it embarked on a major fiscal and credit-fuelled expansion after the crisis, thereby reversing the sharp, crisis-induced drop in prices and giving the commodity boom a new lease of life. On the other hand, easy monetary and financial conditions boosted commodity prices further. And as prices soared, they reinforced the financial booms and easy external liquidity conditions for many commodity producers. The mutually reinforcing feedback gained momentum.

What we have been witnessing over the past year may be the beginning of a major, inevitable and needed realignment in which these various elements reverse course. Domestic financial cycles have been maturing or turning in a number of EMEs, not least China, and their growth has slowed. Commodity prices have fallen. More specifically, a combination of weaker consumption and more ample production has put further pressure on the oil price. In addition, actual and expected US monetary policy tightening against the backdrop of continued easing elsewhere has supported US dollar appreciation. This in turn has tightened financing conditions for those that borrowed heavily in the currency (Chapter III).

We have also seen that this realignment is neither smooth nor steady. Rather, it slows or accelerates as market expectations change. Indeed, since the financial market turbulence in early 2016, oil prices have recovered and the US dollar has lost some of the ground gained earlier. In some cases, these market shifts reflect shocks of a more political nature, such as uncertainties around the UK referendum on continued EU membership. But mostly they are in response to the same underlying forces that have been shaping the global economy for a long time: shifting expectations of monetary policy, the evolution of borrowing costs in major currencies, and further credit-fuelled stimulus in China. In the end, it is the stocks, and far less the shocks, that are driving the global adjustment.

Two factors stand out in this narrative: debt and the cumulative impact of past decisions.

Debt can help better explain what would otherwise appear as independent bolts from the blue (Chapter III). First, it sheds light on the EMEs' slowdown and on global growth patterns. Debt is at the heart of domestic financial cycles and of the tightening of financing conditions linked to foreign currency borrowing. This is most evident for commodity producers, especially oil exporters, who have seen their revenues and collateral strength collapse - hence the large holes in fiscal accounts and big investment cuts. And debt may be one reason why the boost to consumption in oil-importing countries has been disappointing: households have been shoring up their balance sheets.

Second, debt provides clues about the currency movements in the past year and their impact on output. Foreign currency debt reinforces the pressure on domestic currencies to depreciate and hence on the funding currency, largely the US dollar, to appreciate. Chinese companies' sizeable repayments of US dollar debt are an obvious example. And empirical evidence suggests that high foreign currency debt weakens, and may even completely offset, the expansionary trade effect of depreciations (Chapter III).

Third, debt hints at one reason for the oil price weakness beyond the influence of more familiar factors. During the recent commodity boom, oil and gas companies borrowed heavily on the back of unusually easy financing conditions. Their bonds outstanding increased from $455 billion in 2006 to $1.4 trillion in 2014, or by 15% per year; and their syndicated loans rose from $600 billion to $1.6 trillion, 13% per year. Shale producers and EME state-owned oil companies accounted for much of the borrowing. As their financial condition deteriorated, they came under pressure to keep the spigots open to meet their debt service burdens and to hedge even more their dwindling revenues.

Finally, debt may even shed light on the puzzling slowdown in productivity growth. When used wisely, credit is a powerful driver of healthy economic growth. But as the previous evidence indicates, unchecked credit booms can be part of the problem and leave a long shadow after the bust, sapping productivity growth. In addition, debt overhangs depress investment, which weakens productivity further. In turn, weaker productivity makes it harder to sustain debt burdens, closing the loop.

The cumulative impact of past decisions is behind the narrowing room for policy manoeuvre. At any given time, the reduced set of options and political constraints make it tempting to seek to solve the problems by boosting aggregate demand regardless of means and circumstances. But untailored measures may risk wasting ammunition and fail to address the obstacles that hold back growth. If so, over time policy choices become increasingly constrained. And when tomorrow eventually becomes today, one may discover that short-term gains have brought long-term pain and worsened policy trade-offs. We return to this issue below.

Secular stagnation - or financial booms gone wrong?

This possible interpretation of the post-crisis global growth slowdown differs in key respects from one that has been gaining currency - secular stagnation. It suggests rather that the world is better regarded as having suffered a series of financial booms gone wrong. Consider, admittedly in a very stylised form, the main differences in the two views.

The most popular variant of the secular stagnation hypothesis posits that the world has been haunted by a structural deficiency in aggregate demand. This deficiency predates the crisis and is driven by a range of deep-seated factors, including population ageing, unequal income distribution and technological advances. In this view, the pre-crisis financial boom was the price to pay for having the economy run at potential. The key symptom of the malaise is the decline in real interest rates, short and long, which points to endemic disinflationary pressures.

In the hypothesis proposed here, the world has been haunted by an inability to restrain financial booms that, once gone wrong, cause long-lasting damage. The outsize and unsustainable financial boom that preceded the crisis masked and exacerbated the decline in productivity growth. And rather than being the price to pay for satisfactory economic performance, the boom contributed, at least in part, to its deterioration, both directly and owing to the subsequent policy response. The key symptom of the malaise is the decline in real interest rates, short and long, alongside renewed signs of growing financial imbalances.

As discussed in detail in last year's Annual Report, the interpretation of exceptionally and persistently low interest rates is indeed critical. According to the secular stagnation view and prevailing perspectives more generally, these rates are a long-run equilibrium phenomenon - they are necessary to fill a global shortfall in demand that existed even before the crisis. In that view, the behaviour of inflation provides the key signal. According to the view proposed here, interest rates cannot be fully at equilibrium if they contribute to financial imbalances that, at some point, will cause serious economic damage. Likewise, inflation is a highly imperfect gauge of sustainable economic expansions, as became evident pre-crisis. This would especially be expected in a highly globalised world in which competitive forces and technology have eroded the pricing power of both producers and labour and have made the wage-price spirals of the past much less likely.

Adjudicating between these two hypotheses is exceedingly hard. One might make several points against the secular stagnation hypothesis, initially developed for the United States. It is not easily reconciled with that country's large, pre-crisis current account deficit - indicating that domestic demand actually exceeded output. The world in those years was seeing record growth rates and record low unemployment rates - not a sign of global demand shortfalls. Ageing populations also affect supply, not just demand - hence the prospect of lower growth unless productivity growth is raised. Finally, the decline in unemployment rates, in many cases to levels close to historical norms or estimates of full employment, is seemingly more indicative of supply constraints than of demand shortfalls.

But counterfactuals mean that empirical evidence cannot be conclusive, leaving the door open to contrasting interpretations. In this Report, we present several pieces of evidence consistent with the importance of financial booms and busts. We find that financial cycle proxies can help provide estimates of potential output and output gaps in real time - as events unfold - that are more accurate than those commonly used in policymaking based on traditional macroeconomic models and inflation (Chapter V). This finding dovetails with the well known weak empirical link between inflation and measures of domestic slack as well as with the previous evidence on the impact of credit booms on productivity growth. In Chapter IV, we also find that international supply chains can be a powerful mechanism through which global factors impinge on domestic inflation, regardless of domestic capacity constraints. And we find that variants of such financial cycle measures can help tease out estimates of equilibrium interest rates that are higher than commonly thought.

Importantly, all estimates of long-run equilibrium interest rates, be they short or long rates, are inevitably based on some implicit view about how the economy works. Simple historical averages assume that over the relevant period the prevailing interest rate is the "right" one. Those based on inflation assume that it is inflation that provides the key signal; those based on financial cycle indicators - as ours largely are - posit that it is financial variables that matter. The methodologies may differ in terms of the balance between allowing the data to drive the results and using a priori restrictions - weaker restrictions may provide more confidence. But invariably the resulting uncertainty is very high.

This uncertainty suggests that it might be imprudent to rely heavily on market signals as the basis for judgments about equilibrium and sustainability. There is no guarantee that over any period of time the joint behaviour of central banks, governments and market participants will result in market interest rates that are set at the right level, ie that are consistent with sustainable good economic performance (Chapter II). After all, given the huge uncertainty involved, how confident can we be that the long-term outcome will be the desirable one? Might not interest rates, just like any other asset price, be misaligned for very long periods? Only time and events will tell.

Risks

The previous analysis points to a number of risks linked to the interaction between financial developments and the macroeconomy.

The first risk concerns the possible macroeconomic dislocations arising from the combination of two factors: tightening global liquidity and maturing domestic financial cycles. It is as if two waves with different frequencies merged to form a more powerful one. Signs that this process was taking hold appeared in the second half of 2015, when foreign currency borrowing peaked and conditions tightened for some borrowers, especially among commodity producers. After the turbulence at the beginning of 2016, however, external financial conditions generally eased, also taking the pressure off the turn in domestic financial cycles. And in China, the authorities provided yet another boost to total credit expansion in an attempt to stave off a drastic turn and smooth out the needed economic rebalancing towards domestic demand and services. As a result, tensions in EMEs have diminished, although the underlying vulnerabilities remain. Events often unfold in slow motion for a long time and then suddenly accelerate.

Since past crises, EMEs have taken strides to strengthen their economies and make them more resilient to external influences. Their macroeconomic frameworks are sounder; their financial infrastructures and regulatory arrangements are stronger; and flexible exchange rates coupled with large foreign exchange war chests enhance the room for policy manoeuvre. For instance, despite the worst recession on record, Brazil has not yet had an external crisis, in part thanks to its extensive use of foreign exchange reserves to insulate the corporate sector from losses. In addition, at least so far, the increase in loan losses has been contained. More generally, EMEs' foreign currency debt as a share of GDP is smaller than it was before previous financial crises.

Even so, prudence is called for. In some of these economies, the increase in domestic debt has been substantial and well beyond historical norms. The corporate sector has been very prominent, and it is there that the surge in foreign currency debt has concentrated even as profitability has declined to levels below those in advanced economies, notably in the commodities sector (Chapter III). While the reduction in that debt appears to have begun, most notably in China, poor data on currency mismatches make it hard to assess vulnerabilities. The growth of new market players, especially asset managers, could complicate the policy response to strains by changing the dynamics of distress and testing central banks' ability to provide liquidity support. In addition, EMEs' greater heft and tighter integration in the global economy indicate that the impact of any strains on the rest of the world would be bigger than in the past, through both financial and trade channels (Chapter III).

The second risk concerns the persistence of exceptionally low interest rates, increasingly negative even in nominal terms and in some cases even lower than what central banks expected. This risk has a long fuse, with the damage less immediately apparent and growing gradually over time. Such rates tend to depress risk premia and stretch asset valuations, making them more vulnerable to a reversal by encouraging financial risk-taking and raising their sensitivity to disappointing economic news (snapback risk) (Chapter II). They sap the strength of the financial system by eroding banks' net interest margins, raising insurance companies' return mismatches and greatly boosting the value of pension fund liabilities (Chapter VI). And over time they can have a debilitating impact on the real economy. This effect occurs through the channels just discussed, including by weakening banks' lending capacity. But it also arises by encouraging the further build-up in debt and by no longer steering scarce resources to their most productive uses. In effect, the longer such exceptional conditions persist, the harder exit becomes. Negative nominal rates raise uncertainty further, especially when they reflect policy choices (see below).

The third risk concerns a loss of confidence in policymakers. The more time wears on, the more the gap between the public's expectations and reality weighs on their reputation. A case in point is monetary policy, which has been left to shoulder an overwhelming part of the burden of getting economies back on track. Once the crisis broke out, monetary policy proved essential in stabilising the financial system and in preventing it from causing a bigger collapse in economic activity. But despite extraordinary and prolonged measures, monetary policymakers have found it harder to push inflation back in line with objectives and to avoid disappointing gains in output. In the process, financial markets have grown increasingly dependent on central banks' support and the room for policy manoeuvre has narrowed. Should this situation be stretched to the point of shaking public confidence in policymaking, the consequences for financial markets and the economy could be serious. Worryingly, we saw the first real signs of this happening during the market turbulence in February.

The global economy: policy

The previous analysis contains useful clues about policy. Some relate to what policy should do now, not least an urgent rebalancing away from the excessive burden placed on monetary policy. Others relate to the frameworks' architecture. It may be helpful to take them in reverse order, so that one does not lose sight of the final destination when embarking on the journey.

Towards a macro-financial stability framework

The destination is a set of arrangements that systematically incorporate financial stability considerations into traditional macroeconomic analysis - what in the past we have termed a "macro-financial stability framework".2 The framework is intended to more effectively tackle the financial booms and busts that cause so much economic damage. At a minimum, it would encompass prudential, monetary and fiscal policies with strong support from structural measures. Its key operational feature is that authorities would lean more deliberately against financial booms and less aggressively and, above all, less persistently against financial busts.

This more symmetrical policy over financial cycles could help moderate them and avoid the progressive loss of policy room that is arguably a serious shortcoming of current arrangements. One symptom of that loss is the relentless increase in the debt-to-GDP ratio, both private and public. Another is exceptionally low policy rates. While part of their decline in real terms surely reflects secular factors beyond policymakers' control, part probably also reflects policymakers' asymmetrical response, which can contribute to the build-up of financial imbalances and to their long-term costs for output and productivity. This raises the risk of a debt trap, whereby, as debt increases, it becomes harder to raise rates without causing damage. And it means that, over sufficiently long horizons, low interest rates become to some extent self-validating. Low rates in the past help shape the economic environment policymakers take as given when tomorrow becomes today. In this sense, low rates beget lower rates (see below).

How much progress has been made in prudential, fiscal and monetary policies?

Prudential policy

Prudential policy has made the biggest strides. The strategy has been to build arrangements with a strong systemic (macroprudential) orientation based on solid foundations. With the support of the international community, national authorities over the past year have taken further steps to set up or implement macroprudential frameworks designed mainly to strengthen resilience and to restrain the build-up of financial imbalances. While this is still a work in progress, the direction is clearly set.

In bank regulation, a priority in the current year is to finalise the Basel III framework. In doing so, it will be critical to ensure that the level of capital is commensurate with the underlying risks. As recent BIS research confirms, the public debate tends to underestimate the benefits of capital as the very foundation of lending and to overestimate its costs (Chapter VI). Across banks, higher capital goes hand in hand with lower funding costs and higher lending. Stronger banks lend more.

A question that has come to the fore in the period under review is the link between regulatory reforms and market liquidity (Chapters II and VI). In the past couple of years, sharp moves in the prices of the most liquid sovereign bonds in the world - US Treasuries and German bunds - have heightened concerns about the fragility of liquidity conditions. More generally, signs of lower secondary market liquidity in a number of fixed income markets and of smaller broker-dealer inventories have been linked to regulation-induced balance sheet costs and other restrictions. Evidence that financial institutions may be less willing than in the past to commit their balance sheets to the arbitraging of asset pricing relationships has pointed in the same direction (Chapter II).

Such claims must be assessed in a broad context, as changes in market liquidity dynamics have many sources. In the case of fixed income markets, for instance, the spread of electronic trading platforms and of algorithmic and high-frequency trading has played a key role. Likewise, the growth of the asset management industry has probably increased the net demand for liquidity services. And since the crisis, banks' management and shareholders have taken a much more critical view of the risk-return trade-off in the trading business. Even more importantly, liquidity was grossly underpriced pre-crisis, contributing to its evaporation under stress - such gross underpricing is a problem we definitely do not want to revive. The best structural safeguard against fair-weather liquidity and its damaging power is to avoid the illusion of permanent market liquidity and to improve the resilience of financial institutions. Stronger capital and liquidity standards are not part of the problem but an essential part of the solution. Stronger market-makers mean more robust market liquidity.

Fiscal policy

Fiscal policy is a critical missing element in a macro-financial stability framework. Financial stability generally, and financial cycles in particular, have hardly featured in fiscal policy design, whether for short-term macroeconomic objectives or long-term sustainability. Yet history indicates that financial crises can wreak havoc with fiscal positions; conversely, the design of fiscal policy can have a substantial impact on financial stability. And one should not underestimate the risk of a doom loop, whereby weaknesses in public and private sector balance sheets feed into each other. That is why we devote a whole chapter to these issues (Chapter V).

Protecting the sovereign from financial stability risks requires that they be properly identified and mapped into fiscal positions. By hugely flattering the fiscal accounts, financial booms have all too often lulled the authorities into a false sense of security. Outsize and unsustainable booms artificially boost estimates of potential output, growth and sustainable tax revenues and mask the contingent liabilities linked with the public funds needed to support financial repair once a crisis erupts. We suggest ways in which better estimates of underlying fiscal positions can be produced and included in broader assessments of fiscal space.

Conversely, protecting the financial system from the sovereign has several dimensions. One is how to treat sovereign risks in prudential regulation and supervision. A critical issue is the treatment of credit risk, which is under revision in the Basel III framework. The paramount principle is that the prudential standard should be commensurate with the risk. This would also limit the danger of unlevelling the playing field between the private and public sectors, further weakening the growth engine. But the devil is in the details, and the sovereign poses multifaceted risks that give rise to trade-offs. For instance, the sovereign's ability to "print money" reduces, although does not eliminate, credit risk. But it may do so at the expense of inflation risk and, hence, interest rate and market risk. The balance sheet of the sovereign underpins an economy's soundness. One can run, but one cannot hide. Ultimately, there is no substitute for a sound fiscal position with enough policy space to avoid macroeconomic instability and support the financial system if the need arises.

One can then go a step further and think about how best to use fiscal policy more actively to mitigate financial stability risks. One possibility is to make it more countercyclical with respect to the financial cycle. Another, more structural approach is to reduce implicit guarantees, which may encourage risk-taking. Yet another is to use the tax code to restrict or eliminate the bias of debt over equity or to attenuate financial cycles (eg through time-varying taxes in the property market). Each of these complementary options raises well known and tricky implementation challenges. Some options have already been used. They all deserve further in-depth consideration.

Monetary policy

Monetary policy is at a crossroads. On the one hand, there is a growing recognition that it can contribute to financial instability by fuelling financial booms and risk-taking and that price stability does not guarantee financial stability. On the other hand, there is a reluctance to have it play a prominent role in preventing financial instability. The prevailing view is that it should be activated only if prudential policy - the first line of defence - does not prove up to the task. The development of macroprudential frameworks has provided an additional reason to adhere to this sort of "separation principle".

As we have in previous Annual Reports, we argue for a more prominent monetary policy role. It would be imprudent to rely exclusively on (macro)prudential measures. Financial cycles are too powerful - witness signs of a build-up of financial imbalances in a number of EMEs that have actively deployed such measures. And there is a certain tension in pressing on the accelerator and the brake at the same time, as policymakers would do if they, say, cut interest rates and simultaneously sought to offset their impact on financial stability by tightening prudential requirements. True, the relative reliance on monetary and macroprudential measures must depend on circumstances and country-specific features, not least the exchange rate and capital flows (Chapter IV). But the two sets of tools arguably work best when they operate in the same direction. At a minimum, therefore, monetary frameworks should allow for the possibility of tightening policy even if near-term inflation appears under control.

This year we explore this reasoning further by considering in more detail the trade-offs involved in such a strategy (Chapter IV). Under what conditions do the costs of using monetary policy to lean against financial imbalances outweigh the benefits? The answer is not straightforward. But we suggest that some of the standard analyses may underestimate the potential benefits by underestimating the costs of financial instability and the capacity of monetary policy to influence it. In addition, there is a certain tendency to interpret "leaning" too narrowly. Accordingly, the central bank follows a "normal" inflation-oriented strategy most of the time and deviates from it only once signs of financial imbalances become evident. This raises the risk of doing too little too late or, worse, of being seen as precipitating the very outcome one is trying to avoid.

It may be more useful to think of a financial stability-oriented monetary policy as one that takes financial developments systematically into account during both good and bad times. The objective would be to keep the financial side of the economy on an even keel. Some preliminary findings suggest that by augmenting a standard policy rule with simple financial cycle proxies, it may be possible to mitigate financial booms and busts, with considerable long-run output gains. Such a strategy could also limit the decline in the long-run equilibrium or natural rate of interest - the "low rates beget lower rates" phenomenon.

Of course, the issues raise daunting analytical challenges. These findings are subject to a number of caveats and represent just one contribution to the debate. They do suggest, though, that it may be imprudent to implement a selective leaning policy. They also point to frameworks that allow sufficient flexibility not just when financial imbalances are well advanced but throughout the financial cycle, during both booms and busts. And they highlight how current decisions can constrain future policy options.

What to do now?

Our analysis suggests that different policies could have taken us to a better place. Trade-offs have deteriorated and policy options have narrowed. What, then, could be done now?

A key priority is to rebalance the policy mix away from monetary policy - a need the international policy community has now fully recognised. In doing so, though, it is essential to focus not only on the near-term issues but above all on the longer-term ones. But how? Consider, in turn, prudential, fiscal, monetary and structural policies.

For prudential policy the priority, in addition to completing the reforms, is twofold, depending on countries' specific circumstances. In crisis-hit countries, it is essential to finalise banks' balance sheet repair, which is still lagging in a number of jurisdictions, and restore the basis for sustained profitability. To maximise banks' internal resources, where appropriate, restrictions on dividend payments should not be ruled out. Critically, the process may require the support of fiscal policy as the public sector balance sheet is brought to bear on bank resolutions. Ensuring that banks have pristine balance sheets and are well capitalised is the best way to relieve pressure on other policies and improve their traction. Moreover, restoring the banking sector's long-term profitability also calls for eliminating excess capacity, a process for which tight supervision can be the catalyst.

In non-crisis-hit countries, where financial booms are more advanced or have turned, it is essential to strengthen defences against possible financial strains. The authorities should continue to actively rely on macroprudential tools. And they should intensify supervisory vigilance to quickly identify and resolve any deterioration in asset quality.

For fiscal policy, the priority is to help strengthen the foundations for sustainable growth, avoiding destabilising debt dynamics. One mechanism is to improve the quality of public spending, which is already close to record highs in relation to GDP in many countries, notably by shifting the balance away from current transfers towards investment in both physical and human capital. A second mechanism is to support balance sheet repair. A third is to use fiscal space to complement structural reforms. A fourth is to judiciously carry out infrastructure investments, where needed and provided proper governance is in place. A final, key step is to reduce tax code distortions, including the bias towards debt.

In the process, it is important not to overestimate fiscal space. The long-term commitments linked to an ageing society loom large. Debt is generally at an all-time high in relation to income. And the additional buffers needed for financial stability risks can be sizeable (Chapter V). In some countries, the collapse of commodity prices has already revealed the lack of policy room; and in those where unsustainable financial booms are under way, this room may appear deceptively large. The prevailing exceptionally low interest rates should not be taken as a reliable guide to long-term decisions. They provide breathing space, but they will have to return to more normal levels. The risk of having monetary policy become subordinated to fiscal policy ("fiscal dominance") is very real.

For monetary policy, the key is to rebalance the evaluation of risks in the current global stance. The exceptionally accommodative policies in place are reaching their limits. The balance between benefits and costs has been deteriorating (Chapter IV). In some cases, market participants have begun to question whether further easing can be effective, not least as its impact on confidence is increasingly uncertain. Individual incremental steps become less compelling once the growing distance from normality comes into focus. Hence, accumulated risks and the need to regain monetary space could be assigned greater weight in policy decisions. In practice, and with due regard to country-specific circumstances, this means seizing available opportunities by paying greater attention to the costs of extreme policy settings and to the risks of normalising too late and too gradually. This is especially important for large jurisdictions with international currencies, as they set the tone for monetary policy in the rest of the world.

Such a policy shift relies on a number of prerequisites. First: a more critical evaluation of what monetary policy can credibly do. Second: full use of the flexibility in current frameworks to allow temporary but possibly persistent deviations of inflation from targets, depending on the factors behind the shortfall. Third: recognising the risk of overestimating both the costs of mildly falling prices and the likelihood of destabilising downward spirals. Fourth: a firm and steady hand - after so many years of exceptional accommodation and growing financial market dependence on central banks, the road ahead is bound to be bumpy. Last: a communication strategy that is consistent with the above and thus avoids the risk of talking down the economy. Given the road already travelled, the challenges involved are great, but they are not insurmountable.

The need to rebalance the policy mix puts a greater onus on structural policies. Their implementation, of course, faces serious political economy obstacles. In addition, they do not necessarily yield near-term results, although this depends on the specific measures and their impact on confidence. But they provide the surest way of removing impediments to growth, unlocking economies' potential and strengthening their resilience.

Unfortunately, in this area the gap between needs and achievements is especially large. The importance of structural policies has been clearly recognised - witness their salience in G20 deliberations. And so has the need to tailor them to country-specific conditions, beyond the familiar calls for flexibility in goods and labour markets and for fostering entrepreneurship and innovation. Yet the record on implementation so far has been very disappointing, with countries falling far short of their plans and aspirations. Redoubling efforts is essential.

In defence of central banking

The stakes in the required policy rebalancing are high - for the global economy, for market participants and governments, and, not least, for central banks. From its faltering initial steps in the 17th century, central banking has become indispensable to macroeconomic and financial stability. Its performance at the height of the crisis proved this once more. Independence, underpinned by transparency and accountability, allowed central banks to act with the determination needed to put the global economy back on the recovery path.

And yet the extraordinary burden placed on central banking since the crisis is generating growing strains. During the Great Moderation, markets and the public at large came to see central banks as all-powerful. Post-crisis, they have come to expect the central bank to manage the economy, restore full employment, ensure strong growth, preserve price stability and foolproof the financial system. But in fact, this is a tall order on which the central bank alone cannot deliver. The extraordinary measures taken to stimulate the global economy have sometimes tested the boundaries of the institution. As a consequence, risks to its reputation, perceived legitimacy and independence have been rising.

There is an urgent need to address these risks so that central banks can pursue monetary and financial stability effectively. A prerequisite is greater realism about what central banks can and cannot achieve. Without that, efforts are doomed to fail in the longer run. A complementary priority is safeguarding central banks' independence within a broader institutional framework that clearly distinguishes between the responsibilities of central banks and those of other policymakers. This has been fully recognised in the area of financial stability, hence the post-crisis stepped-up efforts to create structured arrangements to pursue this shared task. But it needs further thought in the area of traditional macroeconomic policy, where the line between monetary and fiscal measures has become increasingly blurred. Independence, backed by transparency and accountability, remains as critical as ever.

Conclusion

Judged by historical standards, the performance of the global economy in terms of output, employment and inflation has not been as weak as the rhetoric sometimes suggests. In fact, even the term "recovery" may not do full justice to its current state (Chapter III). But a shift to more robust, balanced and sustainable expansion is threatened by a "risky trinity": debt levels that are too high, productivity growth that is too low, and room for policy manoeuvre that is too narrow. The most conspicuous sign of this predicament is interest rates that continue to be persistently and exceptionally low and which, in fact, have fallen further in the period under review. The global economy cannot afford to rely any longer on the debt-fuelled growth model that has brought it to the current juncture.

A shift of gears requires an urgent rebalancing of the policy mix. Monetary policy has been overburdened for far too long. Prudential, fiscal and, above all, structural policies must come to the fore. In the process, however, it is essential to avoid the temptation to succumb to quick fixes or shortcuts. The measures must retain a firm long-run orientation. We need policies that we will not once again regret when the future becomes today.

1 See J Caruana, "Credit, commodities and currencies", speech at the London School of Economics, 5 February 2016; and C Borio, "The movie plays on: a lens for viewing the global economy", speech at the FT Debt Capital Markets Outlook, London, 10 February 2016.

2 For the first use of the term, see the 75th Annual Report. For a previous elaboration of some of the framework's features, see Chapter I in the 84th and 85th Annual Reports.